Incoming atoms need enough speed to overcome that repulsion, but not so much that they blow the resulting superheavy nucleus apart. Doing that is harder than it sounds because the beam and target nuclei are both positively charged and therefore repel each other. And rather than smashing them together, "We bring two nuclei together so that it is a ‘soft touching,'" Oganessian says. Unrelated to the notorious nuclear power work of the 1980s, Oganessian's cold fusion involves uniting beam and target atoms that are more similar in size than those in traditional elementmaking. Oganessian developed one in the 1970s: cold fusion. Creating most elements in the superheavy realm (beyond 104) therefore requires special tricks. Slamming neon (element 10) into uranium, for example, yields nobelium (102).īut the odds of fusion (and survival) decrease markedly as atoms grow heavier because of increased repulsion between the positively charged nuclei, among other factors. Every so often, the nuclei of the light and heavy atoms collide and fuse, and a new element is born. (The atomic number refers to the number of protons in an atom's nucleus.) Beyond that, scientists must create new elements in accelerators, usually by smashing a beam of light atoms into a target of heavy atoms. The heaviest element found in any appreciable amount in nature is uranium, atomic number 92. "Emotionally," Oganessian says, "it's not easy to take something that gave you a lot. Besides the high cost, constructing the "factory" meant abandoning the old accelerators-which produced so many new elements-to other projects.

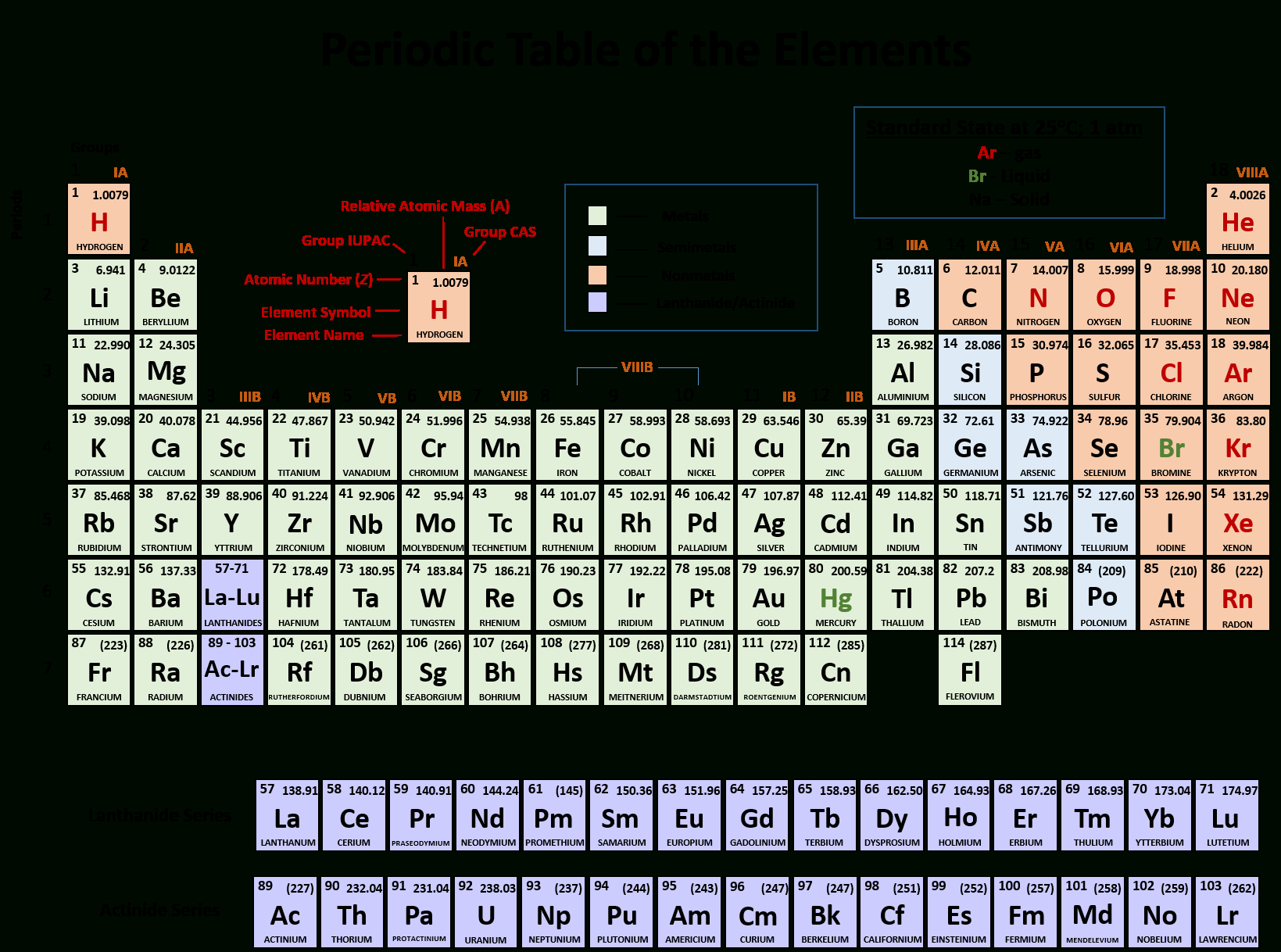

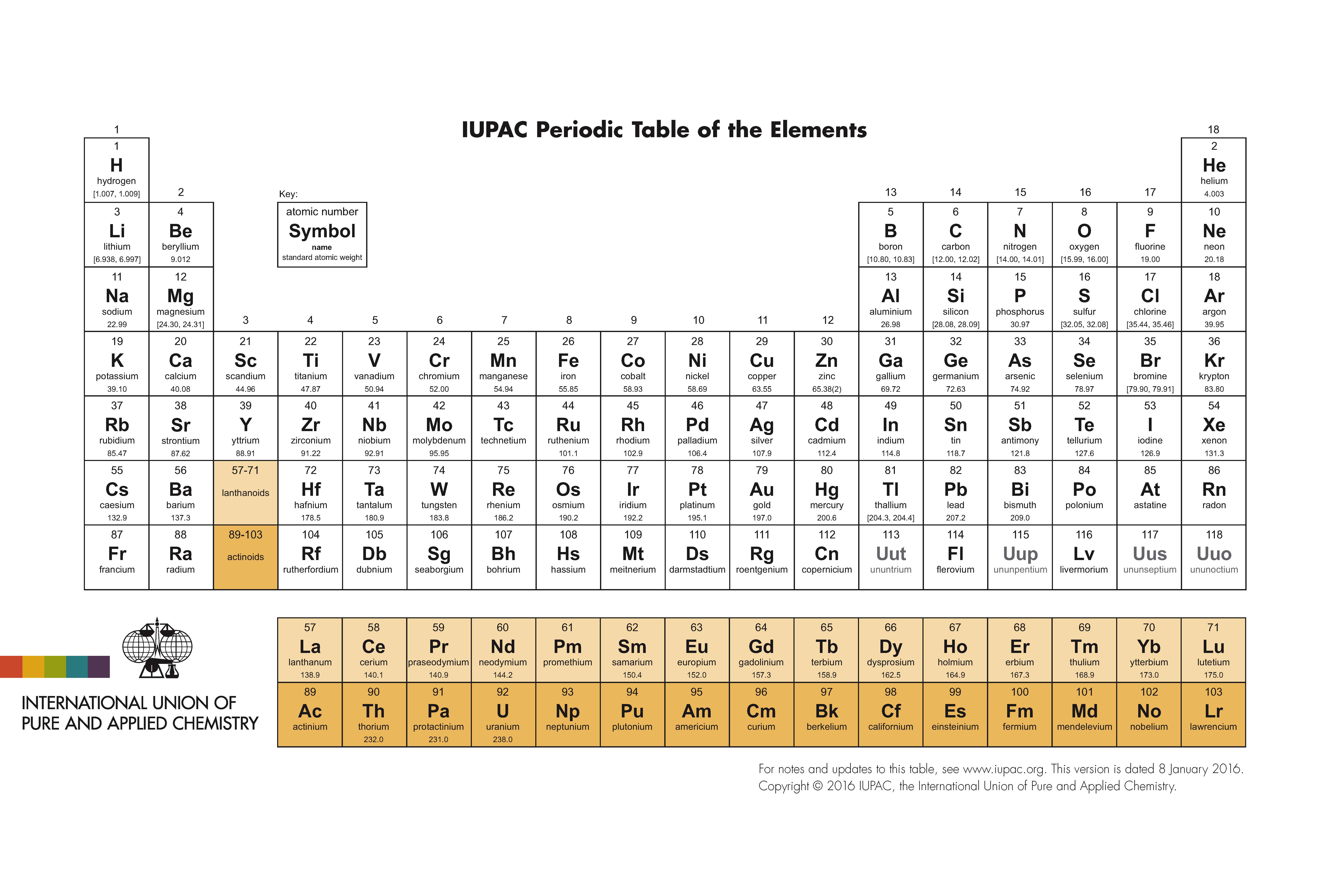

The decision to build the SHEF was tough in some ways. Pushing further into the eighth row also could answer questions that scientists have wrestled with since Dmitri Mendeleev's day: How many elements exist? And how far does the table go? Elements in that row might even destroy the table's very periodicity because chemical and physical properties might not repeat at regular intervals anymore. The new elements would extend the table-now seven rows deep-to an eighth row, where some theories predict exotic traits will emerge. "I personally don't find it exciting, as a scientist, just to produce more short-lived elements," says Witold Nazarewicz, a physicist who studies nuclear structure at Michigan State University in East Lansing.īut to element hunters, the payoff is compelling. Some scientists argue that finding new elements is not worth the money, especially when those atoms are inherently unstable and will disappear in a blink. To push the table further, the lab has built a new $60 million facility, dubbed the Superheavy Element Factory (SHEF), which will start to hunt for element 119, 120, or both, this spring. I feel this deficit."įittingly, no living person has shaped the architecture of the periodic table more than he has, which is why element 118 is called oganesson. He still misses his first love: "I really need something visual with my science. He wanted to study architecture in college until a bureaucratic snafu diverted him into physics. Oganessian, 85, is a short man with bushy white hair whose voice squeaks when he gets excited. The man leading that work is physicist Yuri Oganessian, who has been at Flerov since Nikita Khrushchev signed orders in 1956 to establish a secret nuclear lab in the birch forests here, 2 hours north of Moscow. In various iterations, these accelerators have produced nine new elements on the periodic table over the past half-century, including the five heaviest known elements, up to number 118. At Flerov, particles have the right of way.ĭeservedly so. The pipes you duck under bear warning signs to watch out-not for your head, but for the equipment. Seeing the whole of an accelerator requires some serious gymnastika, scaling perilously steep stairs and dodging anacondas of hanging wires. Or multiple rooms: When equipment doesn't fit, researchers knock holes in walls and thread things through the concrete.

Atomic table full#

And spare parts are everywhere-bins, shelves, whole walls full of metal whatsits in all manner of disrepair.Īll that stuff serves the lab's six particle accelerators, some of which resemble huge mechanical caterpillars, with dozens of tractor-green segments winding through entire rooms.

Tables are strewn with bolts and cleaning fluids, including a vodka bottle half full of ethanol. Scientists in dirty blue smocks walk around while an oil pump thumps out a techno beat.

DUBNA, RUSSIA-From certain angles, the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions here looks more like an auto repair shop than a legendary scientific institute.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)